Brazil’s scientists, already struggling to absorb massive funding cuts, are protesting against another blow: the country’s science ministry has been demoted by interim president Michel Temer, who took over the government on 12 May after a Senate impeachment vote ousted Dilma Rousseff from the presidency.

Among Temer’s first actions was to announce the fusion of the federal Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) with the ministry that deals with telecommunications and Internet regulations. Science is now a main office within a ‘superministry’ led by Gilberto Kassab, a former mayor of São Paulo.

The move, which Temer began hinting at a few days ago, has angered some Brazilian researchers. On 11 May, 13 scientific associations, led by the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC) and the Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC), sent a letter to Temer warning that the fusion would be “detrimental to the country’s scientific and technological development”. Researchers say that it would corrode the authority of the MCTI, which has formed the backbone of federal support for science and innovation in Brazil for the past three decades.

“An administrative reorganization should stem from a vision for the country. It shouldn’t simply be an artificial lumping of disparate activities,” says ABC president Luiz Davidovich. The move is “a step backwards”, he says.

Temer had first raised concern among scientists last week, when he hinted to local media that he might appoint a creationist evangelical bishop to lead the science ministry — a suggestion that led both the SBPC and the ABC to ask Temer to spare the agency in eventual reforms.

“Unfortunately, the science ministry is usually among the first bargaining chips in every new government,” says José Eduardo Krieger, dean of research at the University of São Paulo.

Brazil has had three science ministers in the past 16 months — and each was seemingly appointed for political ends rather than for any particular expertise. In January last year, Rousseff picked Aldo Rebelo, an avowed climate sceptic in the Communist party (the closest ally of Rousseff’s centre–left Worker’s Party). He was followed by Celso Pansera, whose nomination was regarded as an attempt to lure votes from Temer’s Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) party against Rousseff’s impeachment. And Emília Ribeiro, former vice-minister of the MCTI, has been science minister since April 2016.

Pansera admits that such high turnover is detrimental to research. “It gives you a lot of discontinuity,” he says.

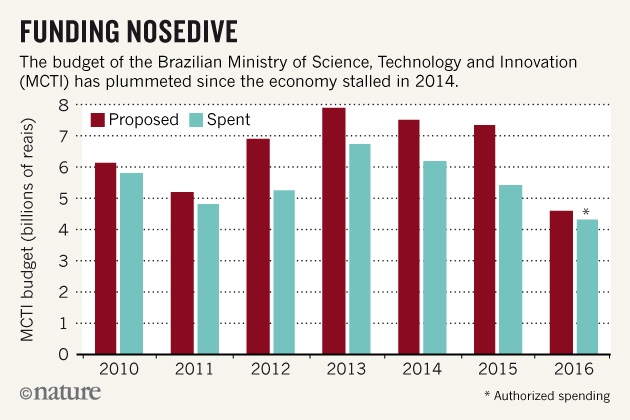

Funding slashed

The most hurtful discontinuity for Brazil’s researchers has been startling cuts to federal funding. Last year, as the nation’s fiscal crisis began to bite, the MCTI’s budget was chopped by some 1.9 billion reais (US$540 million), to 5.4 billion reais. Its budget for this year was set 37% lower than last year’s — and its authorized spending has been chopped by another 6%. The collapse of oil prices and a bribery scandal that involves Petrobras, the behemoth state-run oil company, have further reduced cash flows for Brazilian research, which partly depends on oil revenue.

A major victim of the economic downturn is the flagship exchange programme Science Without Borders, which by the end of 2015 had sent nearly 94,000 Brazilian undergraduate and postgraduate students to leading institutions abroad. The programme intended to send a further 100,000 students abroad by 2018, but its second phase, scheduled to start this year, has been called off.

To revive science spending, the government had authorized the MCTI to negotiate a US$1.4 billion loan from the Inter-American Development Bank, headquartered in Washington DC. But that operation has been reset because of the impeachment, Pansera says. “Now we’ll have to renegotiate everything with the new government’s economic team.”

Research institutes are struggling to survive. At the Brain Institute at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte in Natal, researchers split basic maintenance expenses such as Internet bills among themselves and buy equipment with their own money, says institute director Sidarta Ribeiro.

And some scientists are already planning to leave the country. Suzana Herculano-Houzel, a neuroscie ntist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, launched a crowdfunding campaign last year to buy new parts for a microscope. But she has now decided to move to Vanderbilt University in the United States: this September, she will shut down her lab in Brazil, which had been running for a decade.

ntist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, launched a crowdfunding campaign last year to buy new parts for a microscope. But she has now decided to move to Vanderbilt University in the United States: this September, she will shut down her lab in Brazil, which had been running for a decade.

Brazilian scientists are familiar with economic crises. In the 1990s, budget constraints were the rule, recalls Paulo Artaxo, a physicist at the University of São Paulo. But before the current crisis, the country’s research had been experiencing unprecedented expansion, with funding on the rise and the number of PhD students soaring. In 2011, Brazil jumped to 13th in the world in terms of research-paper production, up from 17th in 2001.

That trend is already reversing, says Rogério Meneghini, a specialist in science metrics and scientific director of SciELO, a subsidized collection of mainly Latin American journals. Brazil’s research-paper production grew at a steady rate of 16% between 2011 and 2014 — but his preliminary figures suggest that it had dropped by 4% in 2015.

“What is cruel about this is that, when you cut off on science, you can never resume from where you stopped”, Krieger says. “You lose position.”

– – – – – – – – – –